I’ve sat on many evaluation panels over the years.

Different universities. Different rooms. Different faces.

But strangely, the pattern is always familiar.

Students walk in carrying posters, prototypes, sometimes with wires still exposed, sometimes with boxes made from recycled lab scraps. They look nervous. Excited. Hopeful. Tired.

And almost every presentation begins the same way.

“This project is about…”

“The objective of this project is…”

I sit back in my chair and quietly think to myself, Ah… here we go again.

Because at that moment, something important is missing.

The Moment Evaluators Lean In or Tune Out

When I evaluate a Final Year Project, I’m not hunting for perfection. I’m not expecting commercial-grade products. I’m not counting how polished the slides are.

I’m listening for one thing.

Do you understand why you built this?

Many students rush straight into objectives, features, and functions. But they forget to set the stage. They forget to frame my mind.

Without a background.

Without a problem that feels real.

Without a pain point that matters.

And when that happens, evaluators start asking questions not because the project is weak, but because the story is unclear.

Help me care first, I always think. Then help me understand.

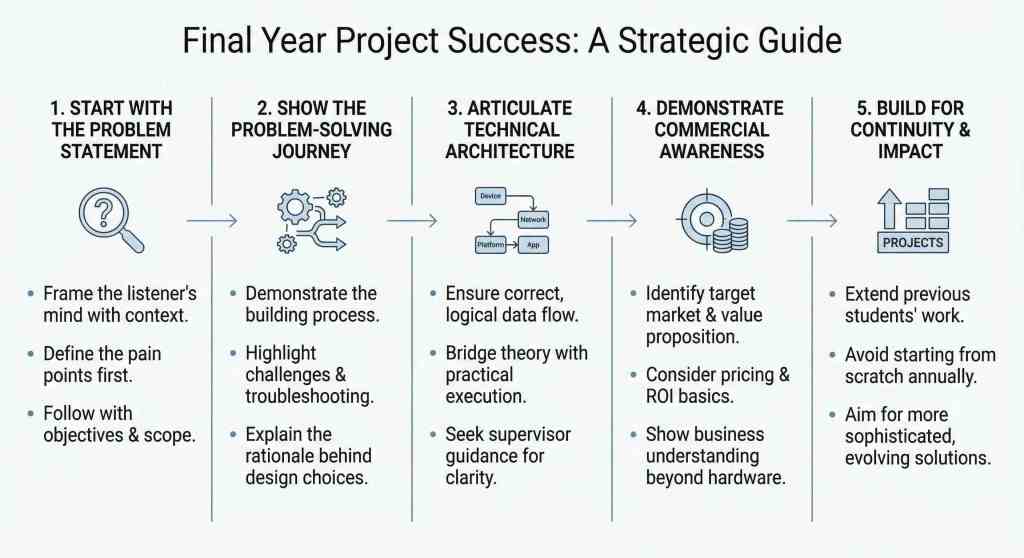

Start With Pain, Not Purpose

The strongest projects I’ve seen don’t start with what was built.

They start with what hurts.

A system that fails silently.

A manual process that wastes hours.

A safety issue nobody notices until it’s too late.

A data gap nobody talks about.

When students explain the background clearly, something shifts. The room wakes up. The evaluator’s brain starts connecting dots.

Only after that does the objective make sense.

Because now, the solution has a reason to exist.

Scope Is Not a Weakness

Another thing I notice again and again.

Projects that look “complete,” but aren’t honest about their limits.

Students are afraid to admit constraints. Limited time. Limited budget. Limited access to hardware. Limited skills.

But here’s the truth.

A clear scope shows maturity.

When you explain what you chose not to build and why, you’re telling me you understand trade-offs. You understand reality. You’re not pretending.

That impresses evaluators more than pretending everything is done.

The Story of Struggle Matters More Than the Result

Some of the most memorable presentations weren’t the ones that worked perfectly.

They were the ones where students said:

“We tried this. It failed.”

“So we changed this.”

“It broke again.”

“Here’s why we finally chose this approach.”

That tells me you didn’t just follow a tutorial. You wrestled with the problem. You learned where things break.

And that’s exactly what real engineers, builders, and problem solvers do.

Architecture Is Not Just a Diagram

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen architecture diagrams that don’t reflect reality.

Devices sending data to nowhere.

Networks are magically working.

Platforms floating without context.

When I ask, “Where does the data go next?”

Silence.

Architecture is not an artwork. It’s a thinking tool.

If you can’t explain how data moves from device to network, from network to platform, from platform to application, then you don’t fully own your system yet.

This is where supervisors play a big role. And this is where students must slow down and really understand what they are drawing.

Prototypes Don’t Need to Look Pretty

Some students apologise for their mock-ups.

“Sorry, sir, this is just a box.”

“Sorry, sir, we used old parts.”

I always smile.

Because that’s not what I’m judging.

What excites me is when students act out real scenarios. When they simulate how users interact. When they demonstrate behaviour, not just hardware.

I still remember sitting inside a car to experience a student-built parking system. That wasn’t about polish. That was about empathy.

The Question That Makes Everyone Nervous

Then comes the part that always makes students laugh nervously.

“So… who would buy this?”

Suddenly, the room gets quiet.

Many students talk about the cost of components. Few talk about customers. Fewer talk about value.

I’m not expecting a full business plan. I’m testing awareness.

Do you understand that solutions exist to be used?

Do you know who benefits from what you built?

Because a project that solves a real problem for a real group of people already has more value than one that only looks good on demo day.

When Systems Break, Thinking Is Revealed

The most important questions often come at the end.

“What happens if the system fails?”

“How do you troubleshoot this?”

“What would you check first?”

These answers reveal everything.

They show whether learning happened.

They show whether the student truly built the system or just assembled it.

In team projects, I watch carefully. Everyone should understand their role. Everyone should be able to support each other. Silence from team members tells its own story.

Forty Years of Change, One Pattern That Remains

I’ve watched student projects evolve from the 1980s until today.

Better tools. Better access. Better exposure.

Yet one problem remains.

Projects restart from zero every year.

Limited budgets force repetition. The same sensors. The same ideas. The same level of impact.

Imagine if universities treated projects as living systems.

One cohort builds the base.

The next improves it.

Another adds data analysis.

Another adds intelligence.

That’s how meaningful systems grow.

Especially in IoT, where data collected over time becomes more valuable than the device itself.

My Advice to Students and Educators

If you’re a student, remember this.

Your project is not judged by perfection.

It’s judged by understanding.

Clarity.

Honesty.

Growth.

Tell the story of your problem.

Explain your decisions.

Show your struggles.

Own your limits.

If you’re an educator or supervisor, help students see beyond grades.

Teach continuity.

Teach systems thinking.

Teach them to build on each other’s work.

Because the real world doesn’t reset every semester.

And the most important lesson a Final Year Project can teach is not how to build something that works.

It’s how to think when things don’t.

Discover more from Dr. Mazlan Abbas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.